-

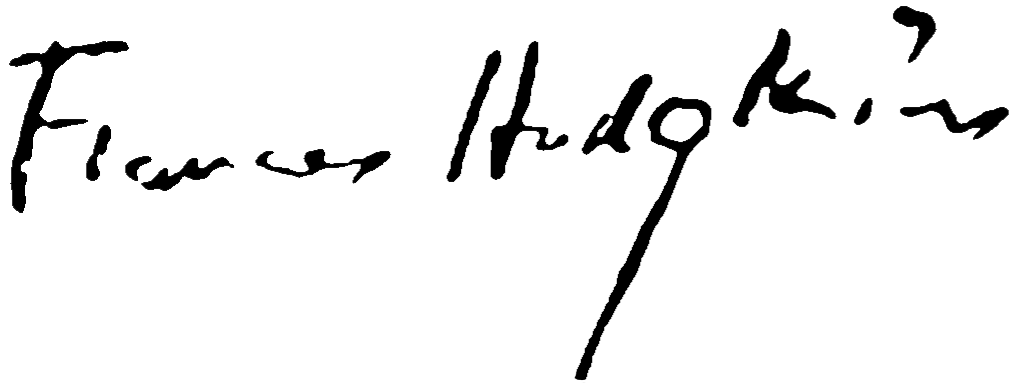

Frances Hodgkins

Christmas Tree , 1945

Oil on canvas, 127 x 101.6 cm

Signed Frances Hodgkins lower right

Provenance

Acquired directly from the artist at Corfe Castle by Dr Leonard D. Hamilton in July 1945

This painting was a feature in the artist’s studio during the war years. Dr Hamilton and his wife bought it in July 1945 after meeting Frances Hodgkins at Corfe Castle and being invited to her studio

Literature

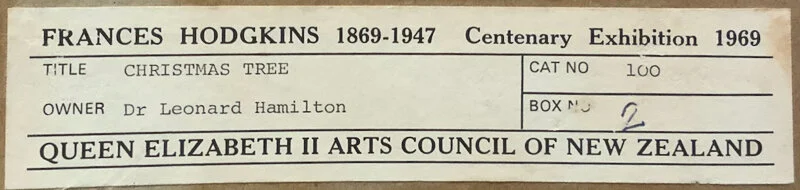

Exhibition catalogue, Frances Hodgkins 1869-1947, Dunedin Public Art Gallery, Arts Council of New Zealand, p. 100

Reference

Frances Hodgkins Database FH1247

(completefranceshodgkins.com)

Illustrated

Exhibition catalogue, Frances Hodgkins 1869-1947, Dunedin Public Art Gallery, Arts Council of New Zealand, p. 100

Exhibited

Frances Hodgkins 1869-1947: A Centenary Exhibition, Queen Elizabeth II Arts Council of New Zealand, Auckland, 1969

This exhibition travelled to:

Christchurch, Robert McDougall Art Gallery, June 1969 Wellington, National Art Gallery, July 1969

Auckland, City Art Gallery, August 1969

Melbourne, National Gallery of Victoria, October 1969 London, Commonwealth Institute Gallery, February 1970

Casting Light

Written by Mary Kisler MNZM

In a letter to her mother from France in 1902, Frances Hodgkins described the difficulties she and her painting companions found when they first arrived at their hotel:

‘I wish you could see our little sitting room – as it was when we first came & as it is now. The first week it was covered in bric-a-brac from floor to ceiling, all sorts of unconsidered trifles in the way of pots & fans & artificial flowers & drapery & ormolu ornaments. We hardly dared speak for fear of breaking something & the dust of ages lay thick on everything. In fear & trembling we suggested to Madam that some of her precious things should be put away for fear of breaking them & to our delight she made a clean sweep & cleared the decks most effectually, & now we have adorned the room with our masterpieces, which hang from every available nail…’

Frances Hodgkins to Rachel Hodgkins, from Patisserie Taffats, Rue de L’Apport Dinan, 21 August 1902 or thereabouts.

In her early approaches to European modernism, Hodgkins was to make further alterations to overstuffed sitting rooms in her need for a clean and spare environment in which to discuss works with painting companions or eager students. Yet as her career progressed and she no longer had to teach, small decorative items were to play a larger part in her painterly subject matter, in part due to her peripatetic lifestyle, where she was constantly packing up and moving on in search of stimulation and refreshing subject matter. And once she had determined on the still life/landscape compositional motifs that finally made her a household name in Britain in the late 1920s, her keen eye was quick to see that the incorporation of another shell or flower or bowl might add just the right note to complete a work to her satisfaction, and catch the viewer’s attention.

Struggling to survive in post-war Britain, in the mid-1920s Hodgkins took up employment as a fabric designer in Manchester. While a short-lived endeavour, she was sent back to her beloved Paris to view the latest designs on display at the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et industriels. Energised by the experience, she renewed the focus on pattern and design that had been integral to her St Ives paintings, which had been influenced by the artists she had been drawn to in Paris before WWI, including Bonnard, Vuillard and Matisse.

Her individual approach to subject matter developed in quite extraordinary ways in the 1930s in her only known ‘self-portrait/still lifes’ painted in the mid-1930s. Rather than the mirror that is the prerequisite for most traditional self-portraits, Hodgkins combined her favourite garments and accessories to represent the self, inter-weaving gloves, hats, scarves, bags, belts and shoes into complex, almost abstract designs, that when teased out provide a richly rewarding and contemporary insight into her personal and creative character. Photographer and friend Douglas Glass summed up her innovate style:

She looked like her own paintings… you’d see Frances walking about the streets and she was like one of her own paintings, sometimes, the most incredible colours put together. In her dress she looked like the ‘with-it’ people of today – all those mad colours put together… She used to have mad hats that you’d think your grandmother wore, you know with birds in them, that sort of thing.

Douglas Glass Interviews by June Opie: Misc MS 167, Hocken Library, 1969, Tape 1,3.

Hodgkins stood out among British modernists in her approach to such motifs. As the 1930s progressed, the detritus found in farmyards and the broader countryside took precedence over the still life/landscape combination that she had favoured earlier on. And when foul weather precluded working out of doors, Hodgkins’ studies of the knickknacks decorating country inns were once more put to further good use. After the dealer (and later friend) Eardley Knollys came across her is Wales, and arranged for her to stay at the local inn, she wrote in thanks:

…how grateful I am to you for introducing me to Mr Morgan who has made it pleasant & easy for me to come & go about the Estate without the suspicious eye challenging me. …I have done masses of work in between showers of torrential rain, in and about the woods & river of Dolaucothy and have even seriously made pictures of the funny chimney ornaments, which do so lend themselves to decoration. I love them – tender silly unarranged things, receptacle for old & faded letters. I always fall for them & always shall…

Frances Hodgkins to Eardley Knollys from the Dolaucothy Arms Hotel,Pumpsaint, October 31 1942.

When it suited her needs, Hodgkins would return to a motif that had given her particular pleasure. Decorative Motif c1934 (first exhibited February 1935) and Christmas Decorations 1935 both include examples of delicate blown glass birds with spun glass tails. These decorations, invented in Germany and first made popular in the mid-19th century, were often finely coated with a silver nitrate so that they glowed with iridescent colour. A single pink bird rests in the foreground of Decorative Motif, while Hodgkins has artfully grouped several birds facing inwards in Christmas Decorations, as if they are involved in a secret avian conversation.

Frances Hodgkins, Christmas Decorations, watercolour on paper, 1935

In 1945, the artist returned again to these fragile little birds in what was to be her last large-scale oil painting. She had kept them intact for over a decade, carefully packed among her few possessions in the care of kindly friends when on the move. In Christmas Tree, a blue and a pink bird take centre stage among other brightly decorated baubles, finely balanced on a small artificial Christmas tree. This was not a mere invention, as the tree can be seen standing on the mantlepiece in her studio at Corfe, in one of the photographs taken by Felix Man for Vogue magazine in the summer of 1945.

In her painting, the faux red holly berries that were glued to the ends of each branch to hide its supporting wires add a further festive note. Whereas the background is treated with looser, broad brushstrokes, each of these elements are accurately and lovingly delineated.

From the early 1930s memory began to play a vital part in the oil or gouache compositions that Hodgkins created in her English studios on her return from her sojourns overseas to the south of France, the Balearic Islands and the Costa Brava in Spain.

As she wrote to her dealer, Duncan Macdonald on her return to Corfe from Tossa de Mar in 1936:

I am back again, at last, & very glad to be back. I came on here, non stop, with all my stuff; it seemed a good idea. I was properly charged – portfolio uncontrollably bulging. Plenty of work ahead for me.

I am looking for a quiet corner where I can settle down & chrystallize [sic] the after glow of my Spanish memories – before they grow dim.

Frances Hodgkins to Duncan Macdonald from Red Lane Cottage, Corfe Castle, Dorset, 25 May 1936.

And memory is central to a deeper understanding of a number of elements included in Christmas Tree. The summer flowers integral to many of her earlier still life compositions tumble among the branches of the tree, reflecting the many places she has journeyed to throughout her career. As a surreal touch, a robin is perched on an abstracted weir, a favourite subject when staying at Geoffrey Gorer’s cottage at Bradford on Tone in Somerset. Observing foaming water and the broader pool beneath obviously gave her pleasure, and in her work, she sought to capture the force and elemental vitality of the water. The long sweeps of blue and white at the bottom of the canvas seem to be a reference to the water that floats into Chairs and Pots, c1938, which derived from her time in Tossa de Mar from 1935-36, while the ochre curved lines to the right of the weir suggest the curved gate of Portal Nou in the great fortified wall of Dalt Vila, in Ibiza, included in Spanish Shrine, 1933-35. The dark ghost of the farm buildings that populate so many of her works, not least both versions of Houses and Outhouses, Purbeck, 1938, also looms into view on close inspection.

Hodgkins may well have known that trees and robins are ancient symbols of the renewal of spring. A nocturne, Christmas Tree is like an advent calendar, each close observation revealing another of its secrets, reflecting a desire for peace and light after the darkness and horror of war. But it is also a valedictory, casting light on her personal satisfaction and quiet pride in a long and remarkable career, one where she had rightly earned the reputation of being one of Britain’s leading modernists.

Label from the back of Frances Hodgkins Christmas Tree

Once acquired, artworks set out on myriad journeys. Christmas Tree was acquired directly from Frances Hodgkins in her Corfe Studio in 1945 by the young and brilliant medical researcher Leonard D Hamilton, the same year that he married fellow Oxford student and feminist Ann Twynam Blake. It is quite possible that Hamilton was familiar with Hodgkins’ work as a child growing up in Manchester. Certainly, the artist had spent the year of 1925 in the same suburb of Rusholme where his family was living. Either way, when Hamilton visited Hodgkins at the very peak of her long career, they would have found much to discuss. Two years earlier his parents had bought him a painting by fellow Mancunian L S Lowry of Pendlebury Mill to hang in his Oxford rooms, and Hodgkins may well have told Hamilton of how she had loved to paint the mill girls in their shawls in her Manchester days.

Leonard D Hamilton with a Lowry painting in his rooms at Oxford. Photograph: Christie’s

The Hamiltons moved to America in 1939, taking their small art collection with them. Hamilton was to become famous for the extraction and provision of DNA that allowed other biologists to discover its double helix structure, while his wife became a psychiatric social worker. Their newfound wealth allowed them to build their art collection, and Frances Hodgkins would have been exultant had she known that ultimately Christmas Tree was displayed in the company of Picasso, Matisse, Bonnard and other artists from her beloved Modern School of Paris.